The Red Ink of Red October

Hassan Malik - Bankers and Bolsheviks: International Finance & The Russian Revolution

The Wall Street Journal, January 22, 2019

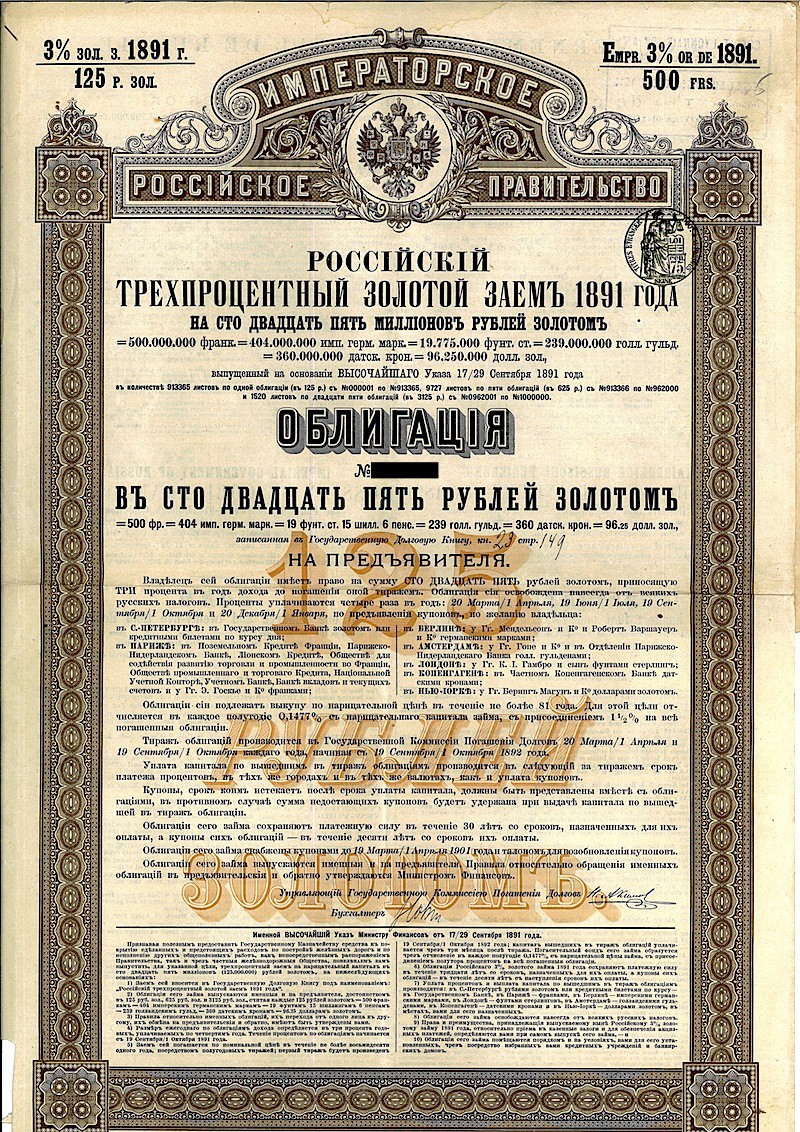

With “Bankers and Bolsheviks: International Finance and the Russian Revolution,” Hassan Malik has written a fascinating study of an overlooked topic—but not a book for emerging markets investors who like to sleep soundly at night. Mr. Malik chronicles the involvement of foreign capital in Russia before and up to the October Revolution. It ends expensively. Shortly after taking power in 1917, the Bolsheviks repudiated Russia’s debts. Adjusted for inflation, this remains the biggest sovereign default in history, made costlier by its completeness. No debts or obligations were “restructured”: With token exceptions, the money was gone for good.

Mr. Malik’s meticulous, forensic account reveals why late Romanov Russia—for a few years the world’s largest oil producer—had been so successful in attracting funding from abroad. Mr. Malik, an investment strategist and financial historian, is more skeptical than many about the contribution made by Sergei Witte, who was Russian finance minister between 1892 and 1903 (before rising higher still). But the surge in Russia’s economic development during those years is beyond dispute. Net national product grew at an estimated compound annual rate of nearly 5%, “very high” for the time, according to Mr. Malik. Other numbers tell a similar tale.

That Russia turned to foreign bond markets during a wave of financial globalization was not “particularly remarkable,” the author notes. That it would become “the largest net international borrower in the world” was, he believes, a different matter. Given the pace of Russian growth, however, and bankers’ perennially Pavlovian response to the whiff of profit, I am not so sure.

There was also the perception at the time that, for all its faults, Russia was “a responsible member of the European family of civilized nations.” As such, the czar’s government was rewarded with more trust than it probably deserved. In 1906 Russia secured a massive loan despite troubling finances, an economic slowdown, a shaky currency, recent military defeat by the Japanese, and something close to outright revolution. More foreign money followed, drawn in by a return to growth. Nevertheless, Mr. Malik argues that late imperial Russia was more fragile than understood then (and now). Debt was piling up and the political system was unstable. It took a huge build-up in defense spending—the silver lining of a cloud about to burst—to revive an economy that was again faltering.

If the attitude of foreign financiers toward Russia up to 1914 can be defended, their behavior afterward is rather harder to explain. By early 1917 Russia was losing World War I, its finances were crumbling, the economy was buckling and the political climate was deteriorating. Despite this, Mr. Malik notes, “the risk premiums on Russian debt relative to Western benchmarks approached multiyear lows.” Wartime politics played their part, and so did moral hazard, thanks to Russian government guarantees (and vague support from its allies). The liberal revolution that overthrew the czar in early 1917 was broadly welcomed as another step in a transformation in which, as Mr. Malik observes, international financiers considered they had long been participating. Maintaining or increasing their presence in a newly liberal Russia would be a “logical continuation” of that role, so that’s what they did.

What ensued, unfortunately, was not the next stage in a benign evolutionary process, but an abrupt break with the past. Foreign investors anticipated radical change, maintains Mr. Malik, but not the direction it took. This was a mistake more forgivable than he implies: There was nothing inevitable about the Bolshevik triumph that fall. The author is right to highlight the probability that, even if the liberals had held on to power, “a fairly significant default” was on the cards. But a default by a liberal regime would have borne no comparison to the Bolshevik default.

Even had the Bolsheviks been able to honor the debt, they would not have done so. This was a matter of principle (why, asked Lenin, repay lenders who financed “the Cossack whip and sword”?) as well as strategy. Debt repudiation was a weapon in the class war, intended to dismantle the economic strength of the bourgeoisie at home and to foment trouble abroad—specifically in France, where investment in Russian securities had spread a long way down the social scale.

Mr. Malik records the insouciance or even optimism of foreign financiers in the face of late 1917’s political turmoil. This may have peaked with “in hindsight . . . one of the most bizarre business decisions in American banking history”—no mean feat: The forerunner of Citibank opened its Moscow branch “nearly three weeks after the Bolshevik takeover.” This was an extreme example of the consequences of some financiers’ misreading of Lenin’s new order, a phenomenon Mr. Malik handles well. Precedent (Russia had never defaulted) suggested the new regime would see reason, as did a conventional understanding of morality and self-interest. Yet bankers and Bolsheviks defined reason, morality and self-interest in very different ways. Lenin’s oddball sect wanted to remake Russia (and the world). If that meant cutting itself off from international capital, too bad.

Mr. Malik criticizes foreign investors for not grasping “the political dimension” of financial support for the czar’s sometimes savagely repressive rule. But their unpopularity with the opposition was somewhat ironic: It overlooked the way in which “apolitical” foreign financing contributed to a modernization that, however unintentionally, subverted the ancien régime. And investors may have paid too much attention to politics later on. One element in the seemingly complacent reaction of international financiers to the February Revolution was a desire to help the liberal reformers. This may have been too much of a gamble but, given what was to come, it was worth taking. Russia’s tragedy was not that it ran out of money, but that it ran out of time.